The Greek prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, is facing his biggest crisis yet as – less than a week after rainstorms left vast tracts of the country’s heartlands under water – his government has come under attack for its handling of the disaster that left 15 dead.

Health experts have described conditions in the flood-stricken Thessaly region – one of Greece’s richest agricultural areas – as ripe for the spread of infectious diseases after a summer of unprecedented heat-induced forest fires.

Public health officials reiterated appeals on Monday for residents in the affected areas to use only bottled water for personal hygiene, drinking and cooking despite ongoing shortages.

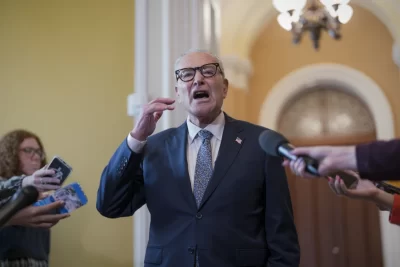

“The economic catastrophe is massive since the productive heart of the country is here,” said Nikos Androulakis, leader of the opposition social democrat Pasok party as he toured the rain-swamped plain of Thessaly on Sunday.

“The responsibilities of the government and [the local] prefecture are very big. It is clear they failed to shield Thessaly from such extreme weather phenomena.”

After Ianos, a rare Mediterranean cyclone which hit the same area three years ago, €240m (£206m) in funding had been allocated for the construction of anti-flood reinforcements, Androulakis told reporters.

“The quality of the anti-flood works that have taken place has to be inspected but [officials] should also apologise for the works that have not happened in recent years,” he said.

On Monday – hours after Mitsotakis announced “immediate” relief measures for flood victims – many were asking where the money had gone.

Greek rescuers work through night to locate villagers trapped by flood

The leftwing main opposition Syriza party, in a statement lambasting what it called the leader’s lack of remorse and self-criticism, said: “Clearly [the prime minister] did not feel the need to give answers about the hundreds of millions that were handed out for infrastructure and anti-flood works.

It said that three years after Ianos, Thessaly was now looking at a bleak future under water and mud. The region generates more than 25% of Greece’s agricultural produce.

Efi Achtsioglou, the front-runner in this month’s race for a new Syriza leader after the party’s routing at general elections in June, accused the government of “throwing [long accepted] flood risk management plans in the rubbish”.

She said: “It ignored European Commission warnings [about works not carried out]. These responsibilities must be taken.”

The sight of flood-stricken villagers being forced to clamber on to the roofs of their homes and wait for days for help because of the failure of rescue forces to properly coordinate themselves has prompted outrage in many quarters.

Described as the worst rainfall in the country’s history, the downpours, named Storm Daniel, dumped a year’s worth of rain on central Greece in 24 hours.

Beyond the loss of life – which could rise from 15 fatalities, as two people are still missing – the torrential rains have left a trail of devastation with roads, bridges, buildings and vital infrastructure uprooted and washed away.

Entire villages remain submerged in waters up to 3 metres deep amid reports of some settlements being “wiped off the map”.

Increasingly, the floods have been called a “national tragedy”, with the media noting that even “biblical catastrophe” seems inadequate in conjuring the extent of the devastation.

Although Greeks accept the natural disaster is unprecedented, they have also chafed at revelations that not enough aircraft, including Super Puma helicopters, were available to conduct search-and-rescue operations when the country spends more than any other EU member state on defence.

In an unexpected indictment of Mitsotakis’s handling of the disaster, the editor of the pro-government Kathimerini newspaper railed that “lightweight” politicians had been put in crucial posts in an excoriating column headlined: “Either we get serious or we sink.”

“The time has come for all of us to put egoism aside: first, the prime minister,” wrote Alexis Papahelas, declaring that if the leader could not find suitable candidates on his own benches he should look further afield.

“We cannot change nature or geography. The point is that we all wake up, from the prime minister to the last citizen, and understand that if we do not come out of our inertia and cynical lethargy, we will end up a ‘failed state’.”

In an extensive report on Monday, Kathimerini said the reality was that flood control projects in central Greece had remained on paper. While roads and bridges damaged by Ianos had been rebuilt, delays in issuing environmental permits had postponed flood protection projects, it said.

Mitsotakis, who was voted into office for a second term after securing a resounding electoral victory, prides himself on his crisis management skills.

The fallout from the floods had caused such consternation that insiders said it was likely the 55-year-old leader would soon push ahead with a cabinet reshuffle in the hope of reshaping his government’s dented image.

The makeover is expected to happen once the PM returns from Brussels where he will appeal for emergency funds to deal with the disaster in talks on Tuesday with the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen.