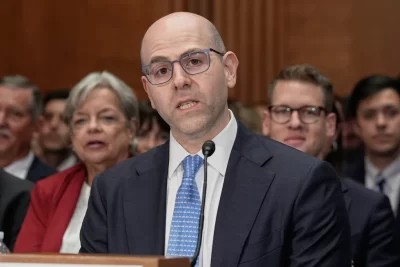

The first thing Greg Jackson did when he arrived in Lewiston, Maine, was to drive through the city, into its neighborhoods, past the crime scene tape and the boarded-up windows, to get a feel for a community reeling from a mass shooting. The deputy director of the new White House office of gun violence prevention was looking for his starting point.

He set to work figuring out what grief and trauma resources were available for families of the victims and where the city could use assistance. He got a briefing from law enforcement. He met with the governor. And he started doling out help.

“Most governors and even city leaders see the federal government as a big machine — there’s so many different levers and processes and contacts,” Jackson said in an interview. “So me just being a navigator and being able to help cut through some of the government jargon or get the proper contact within 15 minutes versus two days was huge.”

“We see this as a critical way to prevent future violence and disrupt the cycle of violence,” Jackson said. “The first way we can prevent violence is to better serve those who have been directly impacted by violence.”

The issue also figures heavily into Biden’s 2024 reelection campaign, which hopes to reach younger voters who are deeply concerned about gun violence. The president has also pushed for a ban on assault weapons.

“This is about common sense,” Biden said last week during a trip to Lewiston. “Reasonable, responsible measures to protect our children, our families, our communities. Because regardless of our politics, this is about protecting our freedom to go to a bowling alley, a restaurant, a school, church, without being shot and killed.”

Biden has called gun violence “the ultimate superstorm,” affecting not just victims but the everyday lives of community members. His administration believes the response should better resemble how the government acts after natural disasters.

As of Wednesday, there had been at least 37 mass killings in the United States in 2023, leaving at least 195 people dead, not including shooters who died, according to a database maintained by The Associated Press and USA Today in partnership with Northeastern University.

But the White House office isn’t intended to help manage only the aftermath of mass killings.

Some 21% of U.S. adults have reported a personal tie to gun violence, such as being threatened by a gun or being a victim of a shooting, according to a 2022 poll by the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Jackson, like many others working in gun violence prevention, has firsthand experience. He was shot about 10 years ago walking down the street in Washington His 19-year-old cousin was shot and killed about a decade earlier. He was on the ground in Buffalo, New York, as a volunteer last year helping manage the fallout after a white supremacist killed 10 Black people at a supermarket.

“I’ve watched a community suffer alone, and how devastating that can be,” he said.

Until now, Jackson said, the only unified response coming from the federal government was via law enforcement. That was helpful, but it did not address businesses losing money because they had to close as police investigated nearby or schools that reopened without enough trauma therapists for students.

“There was a crime response,” he said. “But when you look beyond the law enforcement response, those levers were never pulled in a systematic way until this office was created.”

In Lewiston, late last month, eight people died at a bar, seven more at the nearby bowling alley and three others at hospitals. An additional 13 people were injured in the shootings. Gunman Robert Card, a 40-year-old firearms instructor, was later found dead of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The White House office was established roughly five weeks before the shooting. In that time, Jackson had already set up contacts at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the FBI’s victim assistance center, the Small Business Administration and other federal organizations. On the ground in Maine, he served as the primary federal contact, so local officials didn’t have to wade through a sea of federal agencies.