Patrick Stewart, who famously played a “Star Trek” captain, has boldly gone where no one has gone before — into his past.

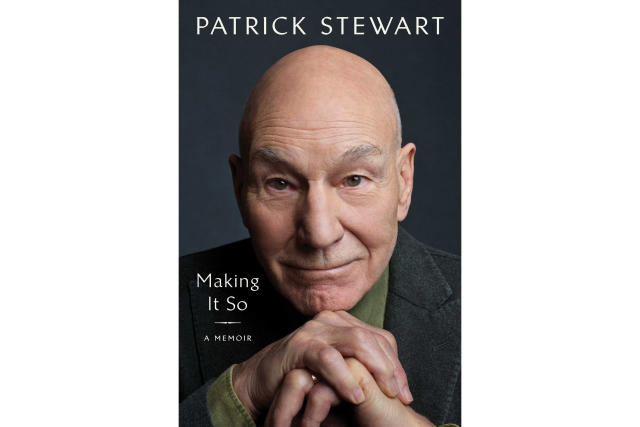

The actor spent much of the pandemic at his computer writing his memoir, and the result is out this fall, “Making It So,” borrowing his catchphrase from “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

“My long-term memory is very strong. It only needed me to turn the key on day one for the door to be open and memory after memory after memory and sensation and sensation and feelings all came scuttling back,” said Stewart, 83, in a Zoom interview from his Los Angeles home.

It is a remarkable story of a boy who grew up poor in the north of England, became a great Shakespearean stage actor and then a sci-fi movie icon aboard the USS Enterprise and the “X-Men” movie franchise.

He grew up without a toilet or a bathroom in his home, sold furniture as a young man, worked up the rungs of regional theater in England — including touring and crushing on Vivien Leigh — before a 14-year-run with the Royal Shakespeare Company and film and TV stardom in Los Angeles.

If one shadow looms, it is that of Stewart’s father, a former regimental sergeant major in the British Army who was prone to outbursts of repeated violence against his mother.

Stewart writes about how he and his older brother, Trevor, braced for nights when their dad came home drunk and angry. “Sometimes it was with an open hand, other times a closed fist. Always he aimed for her head.”

Stewart wonders if the violence triggered his career. “The stage would prove to be a safe space, a refuge from real life in which I could inhabit another person, living in another place and time,” he writes.

Other portraits emerge of people who were kind to Stewart along the way — Paul McCartney, Rod Steiger and Kirk Douglas — and some who were not: Director David Lynch was weird during the original “Dune” shoot and “Star Trek” creator Gene Roddenberry never liked the idea of Stewart piloting one of his starships.

“I wanted to be honest, but I wanted to be so respectful and careful as well. That was the most challenging part of the experience: How much I should say. What should I not say?” says Stewart.

“It’s almost guaranteed that someone is going to come out and say, ‘How dare you? That’s outrageous.’ Well, I’ve brought it on myself. But I did take it very, very seriously.”

One highlight is in 1966 when Stewart, preparing to play in “Hamlet,” is given a one-hour tutorial by the late great director Peter Hall, considered the single most influential figure in modern British theater.

“When the hour was up and I looked at my book, there was nothing but notes scribbled into it,” Steward says. “I realized that he had opened up this text to me in ways that no one had ever done before.”

Another is the grace with which he dealt with premature balding. Despite losing all his hair by 19, Stewart would audition with a hairpiece, remove it and then make his case: Two actors for the price of one.

Stewart dedicates the book to two key school teachers, who fed him a love of Shakespeare and prompted him toward acting. His adoration for Shakespeare would serve him well later in his 40s when he was asked to play Jean-Luc Picard, a 24th century starship commander.

“There is a formality to the way they speak and comport themselves that remind me of numerous Shakespearean situations I’d been in onstage. I should play Jean Luc, I realized, as if he were a character in ‘Henry IV,’ which is about brave men.”

Later in life, Stewart has been exploring his sense of humor, whether dressing as a lobster or lending his voice to Seth MacFarlane animated shows. “People thought it would be fun to see me play against type,” he writes.

Throughout the memoir, Stewart is as critical to himself as any other. Again and again, he admits to mistakes or being unnecessarily stiff, at one point calling himself a “pompous ass.” Stewart describes his relationship with his children as “a work in progress.”

“I needed to do better by the women with whom I was romantically involved,” he writes in one section. “In a life chockablock with joy and success, my two failed marriages are my greatest regret.”

Writing the book became “some of the happiest days of my life,” he says, even though there are a few areas in the audiobook where he had to stop because he was crying.

His wife, Sunny, noticed that he would seem lighter and happier after a writing session. “She said I would come down smiling and kind of glowing because of the whole experience of going back.”