As rural hospitals continue to struggle financially, a new type of hospital is slowly taking root, especially in the Southeast.

Rural emergency hospitals receive more than $3 million in federal funding a year and higher Medicare reimbursements in exchange for closing all inpatient beds and providing 24/7 emergency care. While that makes it easier for a hospital to keep its doors open, experts say it doesn’t solve all of the challenges facing rural health care.

People might have to travel further for treatments for illnesses that require inpatient stays, like pneumonia or COVID-19. In some of the communities where hospitals have converted to the new designation, residents are confused about what kind of care they can receive. Plus, rural hospitals are hesitant to make the switch, because there’s no margin of error.

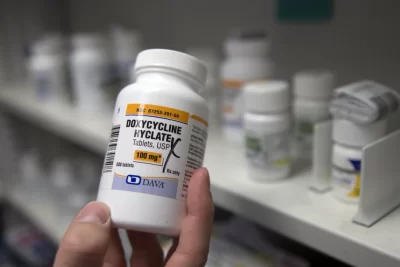

“It’s ironic” that the facilities that might need the most help can’t afford to take the risk, said Carrie Cochran-McClain, chief policy officer at the National Rural Health Association. She pointed to having to give up certain services and benefits, such as a federal discount program for prescription drugs.

The government, which classifies hospitals by type, rolled out the rural emergency option in January 2023. Only 19 hospitals across the U.S. received rural emergency hospital status last year, according to the University of North Carolina’s Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

The majority are in the South, with some in the Midwest, and hospitals in Nebraska and Florida recently started to explore the option.

The designation is aimed at a very specific population, said George Pink, deputy director of the Sheps Center’s Rural Health Research Program, and that’s rural hospitals on the brink of closure with few people getting inpatient care already.

Saving rural care

That was the case for Irwin County Hospital in Ocilla, Georgia, which was the second rural emergency hospital established in the U.S.

Weeks prior to converting, the hospital received at least $1 million in credit from the county so it could make pay employees — money that county board of supervisors chairman Scott Carver doubted he’d see returned.

“We operate on a $6 million budget for the county, so to extend that kind of line of credit was dangerous on our part to some degree,” he said. “But … we felt like we had to try.”

Irwin County Hospital became a rural emergency hospital on Feb. 1, 2023. Quentin Whitwell, the hospital’s CEO, said it was an ideal candidate.

“We’re still finding out what some of the impacts are, given that it’s a new thing,” said Whitwell, who through his company Progressive Health Systems owns and manages six hospitals in the Southeast, most of which are rural emergency hospitals or have applied for the designation. “But the change to a rural emergency hospital has transformed this hospital.”

A combination of state programs and tax credits, plus the new designation, means the hospital has $4 million in the bank, Carver said. Simply put, the work was worth it to him.

Traci Harper, a longtime Ocilla resident, isn’t so sure. About a year ago, she rushed her son to the hospital for emergency care for spinal meningitis.

Because the new designation requires the hospital to transfer patients to larger hospitals within 24 hours, Harper’s son was sent to another in-state facility and three days later ended up getting the care he needed in a hospital in Jacksonville, Florida.

“That’s two hours away,” she said. “The whole time I could have taken him there myself, but nobody told me that.”

‘Barely surviving’

Nebraska’s first rural emergency hospital opened in February in a city called Friend.

Warren Memorial Hospital had reached a breaking point: Federal pandemic relief money had dried up. The city, which owns the hospital, had to start extending lines of credit so hospital employees could get paid. A major street repair project was even delayed, said Jared Chaffin, the hospital’s chief financial officer and one of three co-CEOs.

“Back in the summer, we were barely surviving,” said Amy Thimm, the hospital’s vice president of clinical services and quality and co-CEO.

Though residents expressed concerns at a September town hall about closing inpatient services, the importance of having emergency care outweighed other worries.

“We have farmers and ranchers and people who don’t have the time to drive an hour to get care, so they’ll just go without,” said Ron Te Brink, co-CEO and chief information officer. “Rural health care is so extremely important to a lot of Nebraska communities like ours.”

The first federal payment, about $270,000, arrived March 5. Chaffin projects the hospital’s revenue will be $6 million this year — more than it’s ever made.

“That’s just insane, especially for our little hospital here,” he said. “We still have Mount Everest to climb, and we still have so much work ahead of us. The designation alone is not a savior for the hospital — it’s a lifeline.”

Rural troubles

That lifeline has proven difficult to hold onto for Alliance Healthcare System in Holly Springs, Mississippi, another one of Whitwell’s hospitals and the fourth facility in the country to convert.

Months after being approved as a rural emergency hospital in March 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reneged on its decision.

Hospital CEO Dr. Kenneth Williams told The Associated Press that the government said the hospital isn’t rural because it is less than an hour away from Memphis. A CMS spokesperson said the facility was “inadvertently certified.”

The hospital has until April to transition back to full service, but many in the community of largely retirees believe the hospital has closed, Williams said. Patient volume is at a record low. If the federal payments stop coming, Williams isn’t sure the hospital will survive.

“We might have been closed if we hadn’t (become a rural emergency hospital), so … something had to be done,” he said. “Do I regret all of the issues that for some reason we’ve incurred that the other (hospitals) have not? I don’t know.”

Though Alliance appears to be one of few facilities that have been negatively impacted by converting to a rural emergency hospital, Pink said it’s too soon to know if the federal designation is a success.

“If my intuition is correct, it will probably work well for some communities and it may not work well for others,” he said.

Cochran-McClain said her organization is trying to work with Congress to change regulations that have been a barrier for rural facilities, like closing inpatient behavioral health beds that are already scarce.

Brock Slabach, the National Rural Health Association’s chief operations officer, told the AP that upwards of 30 facilities are interested in converting to rural emergency hospitals this year.