A six-week United Auto Workers strike at Ford cut sales by about 100,000 vehicles and cost the company $1.7 billion in lost profits this year, the automaker said Thursday.

Additional labor costs from the four-year and eight-month agreement will total $8.8 billion by the end of the contract, translating to about $900 per vehicle by 2028, Chief Financial Officer John Lawler said in a company release. Ford will work to offset that cost through higher productivity and reducing expenses, Lawler said.

The Dearborn, Michigan, automaker re-issued full-year earnings guidance that was withdrawn during the strike, but it trimmed its expectations. The company now expects to earn $10 billion to $10.5 billion before taxes in 2023. That’s down from $11 billion to $12 billion that it projected last summer.

Ford said the strike caused it to lose production of high-profit trucks and SUVs. UAW workers shut down the company’s largest and most profitable factory in Louisville, Kentucky, which makes big SUVs and heavy-duty pickup trucks.

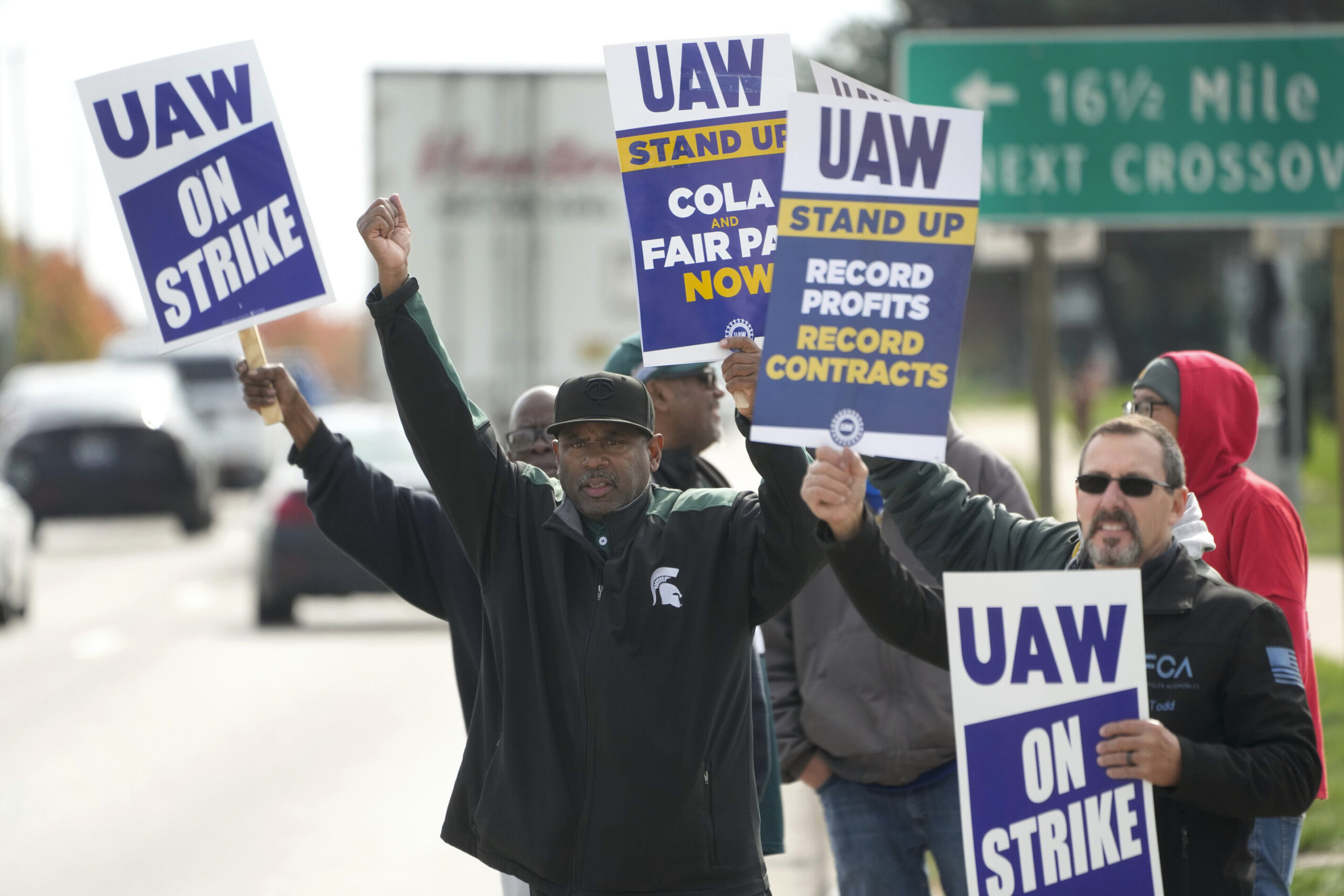

The UAW strike began Sept. 15, targeting assembly plants and other facilities at Ford, General Motors and Jeep maker Stellantis. The strike ended at Ford on Oct. 25.

Ford, as well as rivals General Motors and Jeep maker Stellantis, agreed to new contracts with the UAW that raise top assembly plant worker pay by about 33% by the time the deals expire in April of 2028. The new contracts also ended some lower tiers of wages, gave raises to temporary workers and shortened the time it takes for full-time workers to get to the top of the pay scale.

At the end of the contract top-scale assembly workers will make about $42 per hour, plus they’ll get annual profit-sharing checks.

UAW President Shawn Fain said during the strike that labor costs are only 4% to 5% of a vehicle’s costs, and that the companies were making billions and could afford to pay workers more.

At the Barclays Global Automotive and Mobility Technology Conference Thursday in New York, Lawler was asked about whether Ford would consider something like GM’s $10 billion stock buyback program, which the company announced Wednesday.

Lawler said Ford plans to return 40% to 50% of its free cash flow to shareholders, on top of the current 15-cent per-share dividend. He said the company has faith that executing its plans will increase the stock price.

He also said Ford expects prices to fall next year by about $1,800 for internal combustion vehicles. About $800 of that would come from dealer profits, while Ford would offer $1,000 in discounts, he said.

The company, he said, has to be aware of affordability issues for consumers, who now spend an average of $45,332 on vehicles, according to J.D. Power.

Before the coronavirus pandemic in 2019, people spent about 13.5% of monthly disposable income on vehicles, Lawler said, but that increased to 15.7% in 2022. It’s since dropped to 14.5%, and Ford expects it to return to pre-pandemic levels next year, Lawler said.

Electric vehicle prices, he said, already have fallen faster than Ford or other automakers expected, so he doesn’t see much of a decline next year. But as people who aren’t early adopters start buying EVs, the prices will come down, he said. “They are not willing to pay a premium” over gas powered vehicles, he said.

He foresees EV prices being equal to gas vehicles and said the company is working to reduce EV costs so profit margins equal gas vehicles by 2026 or 2027.

In October Ford announced it would delay $12 billion worth of EV capital spending as the growth rate for EVs started to slow. Lawler said Ford isn’t changing its EV strategy, but is changing tactics “so that we can better match (manufacturing) capacity with demand.”

The company has cut in half the size of a Michigan battery factory, delayed a battery plant in Kentucky and cut manufacturing capacity for electric motors and other components. “It’s not about not moving forward on our electric plans. It’s about the level of capacity that we’re putting in place.”