Henry Winkler’s memoir begins on a Tuesday morning in October 1973, at his first audition for “Happy Days.” He was almost 28 — quite a bit old for a high schooler — and struggling with something he didn’t know had a name.

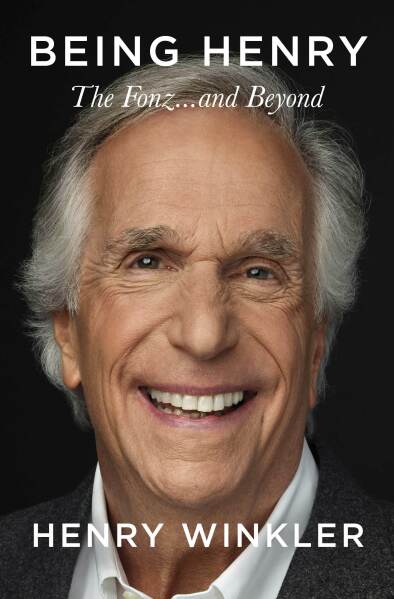

“Being Henry: The Fonz… and Beyond,” released Tuesday by Celadon Books, is a breezy, inspirational story of one of Hollywood’s most beloved figures who became an unlikely TV screen icon and later a champion for those with dyslexia.

Winkler’s 245-page book charts his course chronologically from the Fonz to “Barry” — and the frustrating fallow periods in between — painting a portrait of a man trying to overcome a bitter, loveless childhood and a disability that made reading impossibly hard and simply trying to become a better man.

“I was, in my mind, always a little boy,” he writes. “My real self was like a kernel of corn sheathed in yards of concrete — as insulated as the nuclear material at Chernobyl.”

He describes himself at the “Happy Days” audition as “a short Jew from New York City with a unibrow and hair down to my shoulders, confident about next to nothing in my life.” He had graduated from Yale’s drama school and bagged a few roles despite having difficulty reading.

Later, Winkler dishes, the immense popularity of the Fonz eclipsed anyone else on the show and the network secretly approached him with the idea of spinning off a show or changing the name to “Fonzie’s Happy Days.” Winkler refused.

The end of “Happy Days” brought its own stress for a man who admits that “worrying is my favorite indoor sports.” He writes: “I was terrified of being a flash in the pan. A one-hit wonder. Was I?”

Over the years, there were guest spots on shows like “Arrested Development,” “Royal Pains” and “Parks and Recreation” until finally “Barry,” the show in 2018 that would prove a second tentpole to his career and produce his first primetime Emmy.

In 2003, Winkler branched out into children’s books with Lin Oliver, writing about the adventures of Hank Zipzer, a young boy with dyslexia who overcomes many learning challenges.

The 28-book series “Hank Zipzer: The World’s Greatest Underachiever” was based on Winkler’s own experience with undiagnosed dyslexia. “At the height of my fame and success, I felt embarrassed, inadequate,” he writes.

The memoir is enlivened by an unusual move: Winkler includes long reaction passages from his wife, Stacey, who is pretty brutal about Winkler’s immaturity, his parenting, his own parents and a crippling fear of poverty. “A very big thing I’d learned about Henry was that when he wasn’t working, he was absolutely miserable. Adrift. Insecure. Anxious,” she writes.

It’s telling that Winkler — who writes he has lately benefited from therapy — includes a frank perspective from outside his own head.

There are fun moments throughout: How Winkler came to produce “MacGyver” and how he got fired from directing “Turner & Hooch.” There’s a hysterical section about trying to direct Burt Reynolds in “Cop & ½” and, while Winkler is a nice guy, he’s still capable of throwing some shade at Michael Keaton.

He wonderfully captures the late Robin Williams — “within 42 seconds, I knew, I was in the presence of greatness” — and how CBS made Ron Howard so mad during “Happy Days” that he became a film director almost out of spite.

But one figure looms over this book and career — the Fonz, whose moody expression fills the back cover. Winkler by the end has come to peace with his creation.

“For a long time after ‘Happy Days,’ I was saddened that the world could only see me as the Fonz,” he writes. “But I never lost sight of what the character gave me — a roof over my head, food on the table, my children’s education — and how much it gave me in terms of introducing me to the whole world.”