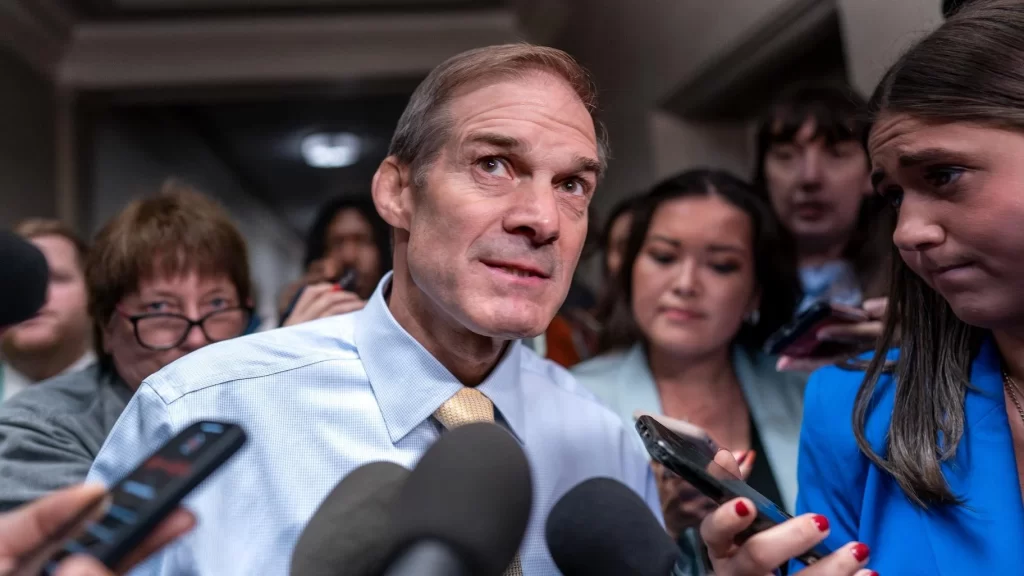

Rep. Jim Jordan has such a reputation as a political brawler that former House Speaker John Boehner once said he’d never met someone “who spent more time tearing things apart.”

Now, nearly a decade after Boehner stepped down in the face of a conservative revolt, it is Jordan, of Ohio, who is trying to bring the Republican Party together to win the speaker’s gavel.

A favorite of former President Donald Trump and darling of the party’s rabble-rousing base, Jordan’s path to the U.S. government’s third-highest office is by no means certain in a House Republican conference riven by conflict following the ouster two weeks ago of former Speaker Kevin McCarthy. To win, Jordan will need support from nearly every House Republican, having few votes to spare in a chamber they only narrowly control.

Should Jordan succeed, it would help cement the far right’s takeover of the Republican Party and trigger fresh conflict with Democrats over the size and scope of government. But a Jordan speakership would also come with baggage that could present a challenge to Republicans as they labor to hold their House majority in next year’s election, an effort that will likely hinge on drawing support from moderate voters in swing districts.

Some members of Congress — including those in his own party — label Jordan an extremist unworthy of the speakership, pointing to his active role in Trump’s bid to stop the certification of the 2020 presidential election, as well as his refusal to honor a congressional subpoena about the Jan. 6 attack at the Capitol. Further in his past, Jordan continues to be questioned over his alleged knowledge of sexual abuse in the wrestling program at Ohio State University — an accusation he adamantly denies.

“If the Republicans decide that Jim Jordan should be the speaker of the House,” Cheney, of Wyoming, said during a recent speech, “there would no longer be any possible way to argue that a group of elected Republicans could be counted on to defend the Constitution.”

Jordan has defended his bare-knuckled approach as rooted in principle, a message that resonates with conservatives who have long accused GOP leaders of capitulation.

“One person says disruption,” Jordan told The Associated Press in 2017. “We like to say we’re doing what we told the voters we were going to do.”

Jordan, a 59-year-old father of four, was born near Dayton in western Ohio. He was a four-time state wrestling champion in high school and a two-time NCAA champion at the University of Wisconsin in the 1980s. That helped him land a coaching job at Ohio State University before his election to the Ohio legislature in the mid 1990s.

His conservatism and zeal for a political fight were evident in early clashes with GOP legislative leaders, as well as with Republican Gov. Bob Taft.

When he decided to pursue a state Senate seat in 1999, he faced opposition from the GOP establishment and from Boehner, then a four-term congressman, who supported a rival. Jordan easily won, ousting a veteran state representative with nearly 60% of the vote. Jordan was elected to Congress several years later, in 2006.

After the tea party wave swept Republicans to power in 2011, the roles reversed, and Jordan was among the conservatives who were frequently Boehner’s tormentors.

Jordan was the founding chairman in 2015 of the House Freedom Caucus, a group of conservative hardliners who eventually pressured Boehner to step aside. More than eight years later, members of the group were instrumental in McCarthy’s removal, a stunning outcome and testament to the group’s outsized power.

But it is Jordan’s past as a wrestling coach — a sport he described as “good for a society” — that has posed one of his biggest political liabilities.

In 2018, several former athletes he coached at Ohio State came forward to describe a lurid atmosphere surrounding the school’s wrestling program when Jordan was an assistant coach. The allegations centered around sexual misconduct by Richard Strauss, a doctor who was on the faculty and medical staff.

Jordan would “even make comments: ‘This guy better not touch me,’” Dunyasha Yetts, one of the wrestlers, told AP in 2018.

A subsequent investigation found Strauss, who died by suicide in 2005, groped or sexually assaulted nearly 200 students, many of them wrestlers seeking medical care. Since then, even more former wrestlers Jordan coached have come forward to say that Jordan was aware of the doctor’s conduct but did nothing to stop it, which Jordan denies.

“It’s false. I never saw, never, heard of, never was told about any kind of abuse,” Jordan told Fox News in 2018, suggesting that the allegations against him were politically motivated. “What bothers me the most is the guys that are saying these things, I know they know the truth.”

Adam DiSabato, a former Ohio State wrestling captain and brother to one of the early whistleblowers, offered an unsparing assessment during a 2020 legislative hearing in Columbus. DiSabato testified that he repeatedly urged Jordan and others on the coaching staff to intervene.

“Jim Jordan called me crying … begging me to go against my brother,” DiSabato said, referring to a call he said he received after the abuse allegations first became public. “He’s throwing us under the bus — all of us. He’s a coward.”

Ohio State has since doled out tens of millions of dollars in settlements. Jordan’s political committee paid $84,000 to a conservative public relations firm in 2018 to help manage the fallout, campaign finance disclosures show.

Unlike many in Congress, Jordan has not adopted some of the flashier trappings of office, appearing regularly in a blue button-up and gold tie, sans jacket and with his shirt sleeves rolled up. Nor, unlike many of his peers, does Jordan appear to have experienced a dramatic improvement in his personal finances while serving in Congress, public financial disclosures show.

When Jordan first entered Congress, his wife, Polly, earned a modest salary from a western Ohio school district while he relied on a mid-five-figure income from a deferred compensation plan. His most recent disclosure, filed last year, show Jordan’s net worth has improved only slightly, thanks to his $174,000 salary as a congressman and royalties from a political memoir.

“It’s true, retail legislative activity for him, so there’s no like, ‘I’m gonna buy a house in Washington and live there,’” said Ohio Senate President Matt Huffman, a longtime ally. “He’s doesn’t have any interest in that.”

Jordan’s skill set proved particularly useful in the politically charged years after Trump won the White House.

His allegiance was on full display during the Justice Department’s investigation into potential coordination between Russia and Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, when he used his platform on the House Judiciary Committee to rail against the probe as politically motivated and to attack the law enforcement officials who supervised it.

In recognition of Jordan’s growing influence, Republicans moved him to the House Intelligence committee during the first impeachment proceedings against Trump in 2019. And when Republicans won the House in last year’s election, Jordan secured the chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee, one of the most prestigious posts in Congress — and one well-suited to his combative style.

In tense hearings this year, Jordan has sparred with Cabinet secretaries, FBI officials and ambassadors alike, accusing them all of taking part in a “weaponization” of government against conservatives. Jordan comes to the hearings with a wrestler’s mindset, trying to anticipate his opponents’ moves ahead of time during preparatory sessions in his Capitol Hill office.

Jordan is also among the Republicans leading the impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden. Republicans say the investigation is needed to root out whether the Biden family corruptly profited from their connections in Washington.

But it was in the period after Trump lost the election to Biden in 2020 that Jordan’s strongest connections to the former president were forged, with Jordan repeatedly casting doubt on the outcome of the contest while organizing the House Republican response.

Documents obtained by Congress through its investigation of the attack offer a window into his involvement in Trump’s bid to stay in office.

Days after the election, Jordan traveled with fellow GOP Rep. Scott Perry to Pennsylvania to meet with the Republican state House speaker, where the two congressmen “raised some questions regarding what I’ll call the legal process,” then-Speaker Bryan Cutler told investigators.

On Dec. 21, 2020, Jordan was among those attending a White House meeting focused on pressuring then Vice President Mike Pence to use his ceremonial role presiding over the electoral college to overturn the election, according to documents from the investigation.

Jordan also hosted a Jan. 2, 2021 conference call with the White House to discuss logistics for Jan. 6, including Republican plans to object to the election’s certification, according to call logs and testimony from Cassidy Hutchinson, an aide to Trump’s chief of staff Mark Meadows.

Jordan also called Trump twice on Jan. 6 — both before and after the attack.

During Trump’s speech that day, which preceded the Capitol attack, he singled out Jordan for praise.

“There’s so many weak Republicans. And we have great ones — Jim Jordan and some of these guys, they’re out there fighting,” Trump said. “The House guys are fighting.”

In the days after the Capitol was attacked, Jordan raised the possibility of getting presidential pardons for members of Congress, though he never directly asked for one for himself, Hutchinson told the congressional committee.

A week later, Trump presented Jordan with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.