Los Alamos was the perfect spot for the U.S. government’s top-secret Manhattan Project.

Almost overnight, the ranching enclave on a remote plateau in northern New Mexico was transformed into a makeshift home for scientists, engineers and young soldiers racing to develop the world’s first atomic bomb. Dirt roads were hastily built and temporary housing came in the form of huts and tents as the outpost’s population ballooned.

The community is facing growing pains again, 80 years later, as Los Alamos National Laboratory takes part in the nation’s most ambitious nuclear weapons effort since World War II. The mission calls for modernizing the arsenal with droves of new workers producing plutonium cores — key components for nuclear weapons.

Some 3,300 workers have been hired in the last two years, with the workforce now topping more than 17,270. Close to half of them commute to work from elsewhere in northern New Mexico and from as far away as Albuquerque, helping to nearly double Los Alamos’ population during the work week.

While advancements in technology have changed the way work is done at Los Alamos, some things remain the same for this company town. The secrecy and unwavering sense of duty that were woven into the community’s fabric during the 1940s remain.

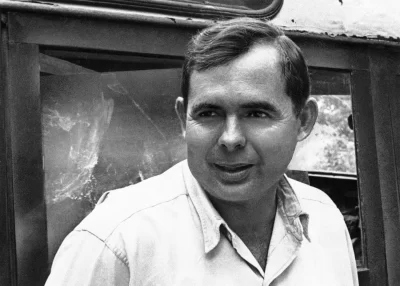

“What we do is meaningful. This isn’t a job, it’s a vocation and there’s a sense of contribution that comes with that,” Owen said in an interview with The Associated Press following a rare tour of the facility where workers are preparing to piece together plutonium cores by hand. “The downside is we can’t tell people about all the cool things we do here.”

While the priority at Los Alamos is maintaining the nuclear stockpile, the lab also conducts a range of national security work and research in diverse fields of space exploration, supercomputing, renewable energy and efforts to limit global threats from disease and cyberattacks.

The welcome sign on the way into town reads: “Where discoveries are made.”

The headline grabber, though, is the production of plutonium cores.

Lab managers and employees defend the massive undertaking as necessary in the face of global political instability. With most people in Los Alamos connected to the lab, opposition is rare.

But watchdog groups and non-proliferation advocates question the need for new weapons and the growing price tag.