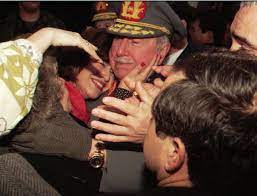

The world remembers Gen. Augusto Pinochet as the dictator whose regime tortured, killed and disappeared 3,065 people in the name of fighting communism.

But as Chile marks the 50th anniversary next Monday of the coup that brought Pinochet to power for almost 17 years, many in the country don’t see it as a dark day. Amid a weak economy and a surge in violent crime, recent polls show that many Chileans don’t think human rights are as much of a priority.

They are grappling with what they see as Pinochet’s complicated legacy at a time when a large number have told pollsters they are losing faith in democracy.

“Before, there wasn’t as much wickedness as there is now,” said Ana María Román Vera, 62, who sells lottery tickets. “You didn’t see as many robberies.”

A July poll by the Center for Public Studies, a Chile-based foundation, found that 66% of respondents agreed with the statement that rather than worry about the rights of individuals, the country needs a firm government. That is more than double the 32% who agreed with the statement fewer than four years ago.

“There should be an overwhelming majority of Chileans who denounce the dictatorship and the military coup and acknowledge that the military destroyed democracy,” said Marta Lagos, director of the regional polling firm Latinobarómetro and founder of pollster Mori Chile. “That would be the normal situation in a normal country. But that’s not the case.”

Late last month, leftist President Gabriel Boric unveiled what will effectively be the first state-sponsored plan to try to locate the approximately 1,162 victims of the dictatorship who remain missing.

Yet even as Boric’s government and human rights organizations plan events to mark the coup anniversary, many in Chile don’t appear to see the ousting of a democratically elected leader as wrong.

A poll earlier this year by Lagos’ firm found that 36% of Chileans believe the military “freed” Chile “from Marxism” when it deposed leftist democratically elected president Salvador Allende, who came into power in 1970 and killed himself the day of the coup. The poll found that 42% said the coup destroyed democracy, the lowest number since 1995.

Pinochet led the coup at a time when the country was mired in an economic crisis that included scarcity of food and galloping inflation that reached an annual rate of 600%. When the military took over it implemented a free-market economy that suddenly meant those with means could go on a consumerism binge even as the poverty rate soared.

Retired accountant Sergio Gómez Martínez, 72, said that “fortunately, Augusto Pinochet led the coup” against Allende’s socialist government. He argued that his economic wellbeing improved under the right-wing military government “because there was order, employment, and the countryside and industries began to produce.”

Repression was unleashed on opponents on the day of the coup. On the days that followed, Congress was shut down and political parties were dissolved as the military junta snatched control of all aspects of society. Those opposed to the regime were regularly imprisoned and tortured and hundreds of thousands were forced into exile.

Gómez said the human rights violations of the Pinochet years “could have been avoided” but they do not seem to be at the centerpiece of his memory of the years of Pinochet’s rule, when by some estimates around 200,000 citizens went into exile for political reasons and some 28,000 opponents of the regime were imprisoned and tortured.

He’s hardly alone. Almost four in 10 Chileans think Pinochet’s 1973-1990 rule modernized the country and 20% see the dictator as one of the best rulers of 20th-century Chile, according to the Mori survey.

A regional survey by Latinobarómetro this year found that only 48% of Latin Americans think that democracy is preferable to any other form of government, which marks a 15-point drop from 2010.

Across Latin America, strongmen like El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele are gaining popularity. Bukele has gained an ardent following due to his severe crackdown on gangs despite a record of human rights abuses.

Boric, meanwhile, has seen a sharp plunge in his approval ratings ever since he swept into power in March 2022 as Chile’s youngest-ever president at 36 following widespread student-led street protests that put on display how the economic inequalities borne from the dictatorship lived on. Citizens broadly rejected an effort last year to replace the country’s dictatorship-era constitution with what would have been one of the world’s most progressive magna cartas, and later went on to elect conservatives to write the next draft of the document.

Efrén Cortés Tapia, a 60-year-old painter, said his most vivid memories about the dictatorship years was not just the “repression” but also “not being able to listen to the music of forbidden folklore groups.” For him, the dictatorship led to “limits in the cultural development” as well as “fear and dread.”

Even as Chilean society grapples with its mixed feelings over the dictatorship, more is being learned about the repression of the years through the courts.

There are around 1,300 active criminal cases for human rights violations during the dictatorship and some 150 are serving sentences in Punta Peuco Prison, a facility exclusively set aside for those guilty of dictatorship-era crimes.

Boric’s administration is also looking abroad for answers, pushing the United States to declassify documents that can help shed light on the role Washington played in the coup it supported.

In late August, the CIA declassified portions of the President’s Daily Briefs related to Chile from Sept. 8, 1973 and Sept. 11, 1973 that confirm then-President Richard Nixon was briefed on the possibility of a coup.

During a recent visit to Chile, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat from New York, said it was “very important … to acknowledge and reflect on the role of the United States” in the coup.

Pinochet remained in power until 1990, stepping down after a majority of Chileans voted against military rule in 1988. But he did not disappear and immediately became commander-in-chief of the Army until 1998 and later became a lifelong senator, a position he created for himself. He resigned in 2002 and died in 2006 without ever being convicted in Chilean courts, although he was detained for 17 months in London on the order of a Spanish judge.

“Chileans got used to living with Pinochet,” Lagos said. “Pinochet, I believe, is the only dictator in Western contemporary history, during this century and the last century, who, 50 years after his coup, is still appreciated by 30 or 40% of a country’s population.”

——-

Politi reported from Buenos Aires, Argentina.