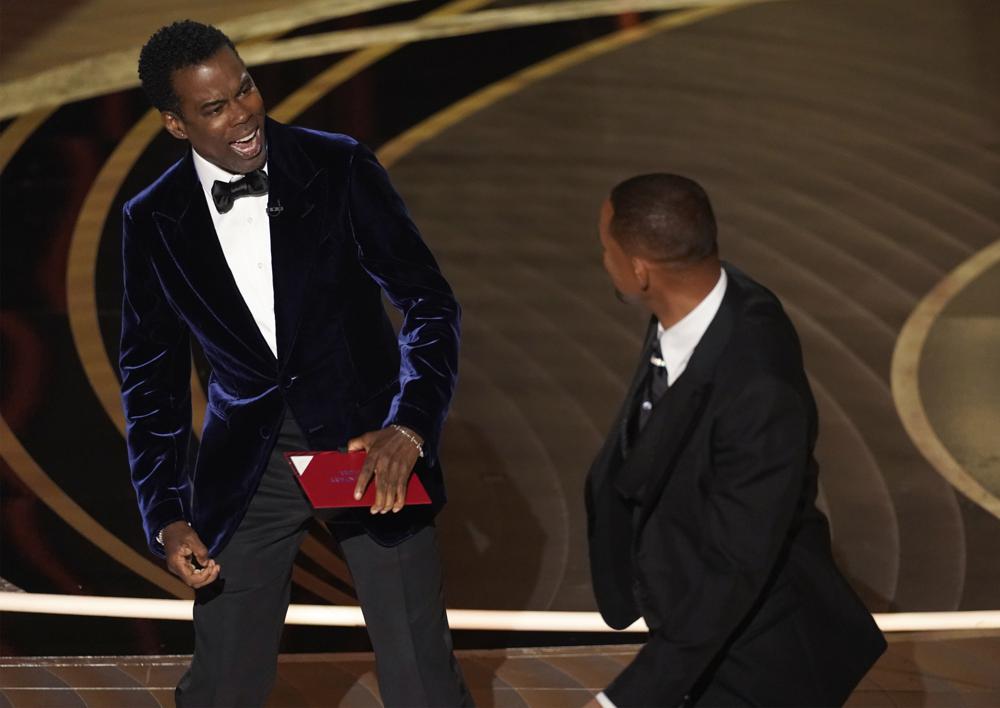

They talked of the specifics of the altercation (“Rock barely moved”). Of its apparent artifice (“It just looks like Chris arched his back the way they do in stage combat”). Of the participants (“Was this just amazing acting?”). Some who watched were just stunned (“Wait that wasn’t staged??”), others openly critical (“a pathetic attempt to get some viewers to tune in”).

Hollywood, the illusion factory, had churned out some unexpected reality at the Oscars. And — surprise! — a lot of people thought it was another illusion.

“It’s not at all surprising to me that the first response is, `Oh, this must be a bit, right? This must be scripted,’” says Danielle J. Lindemann, author of “True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us.”

“We are always looking for these authentic moments. … We feel kind of a triumph when we see something that was actually real,” says Lindemann, a sociologist at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. “But when we encounter what is really an authentic moment, we have the skepticism about it.”

Is it any wonder? After all, we exist in a culture where clothing factories pre-rip blue jeans to make them look “distressed” — like they’ve been worn and frayed through years of actual life experiences. Where followers on Twitter — or faces appearing in your LinkedIn feed — might not be actual people at all. Where lip-syncing in “live” performances — not too long ago a major faux pas — now passes with barely a second look.

Next month heralds a new Nicolas Cage movie starring Nicolas Cage playing Nicolas Cage — or, more accurately rendered, “Nicolas Cage.” It’s the latest in a long tradition of stars portraying themselves (the actual director Cecil B. DeMille appearing in the fictional 1950 movie “Sunset Boulevard,” John Malkovich playing “John Malkovich” in 1999′s “Being John Malkovich,” Bill Murray playing “Bill Murray” in 2009′s “Zombieland”).

Each asks, in short: Where does actor end and performance begin? Or is the line a blurred and muddy one?

That’s what produced some of the confusion Sunday night in media both social and professional: Was this a scripted skit, embedded in a nonfiction show that itself is designed to reward the pinnacles of artistic artifice? One in which Will Smith and Chris Rock played “Will Smith” and “Chris Rock”? Or was it what it actually (apparently) turned out to be — real anger and violence, both genuine and unscripted, playing itself out on stage?

For every person who frame-grabbed in service of proving fraud, another made an equally intense case for the opposite — sometimes using the same evidence.

“We are so used to things being scripted,” says Marty Kaplan, director of the Norman Lear Center at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, which studies the impact of entertainment on society. “And we’re kind of hip and savvy about these things, except we’re not.”

“This one pierced the veil,” Kaplan says. “It was like a rent in the fabric of reality.”

Part of it is that awards shows are different. In the wilds of entertainment, they’ve long been a unique beast — a moment when stars convene under their own names, but still performing for the cameras and the crowds.

They’re not documentary, exactly (though they have elements of it). They’re not mockumentary (though they can certainly veer in that direction). Like Hollywood itself, they’re a stew of their own myths and realities, a high-end variety show where the identities of the winners, the fabulous outfits and the remarks are the planned and generally mannered narrative engines. Until Sunday night, when they weren’t.

“Awards shows have a certain kind of organization and protocol. You’re supposed to act in a certain kind of way,” says Shilpa Davé, a media studies scholar at the University of Virginia. “We’re not used to seeing this in real time on these kinds of shows. We always see them in movies — we see them performing this, but not really doing it.”

Live events, particularly sports, are generally still perceived as trustworthy, Davé says, because they’re happening in real time and “you can make your own assumptions about what you’re seeing.” But Sunday’s events — particularly since the profane audio was bleeped out for U.S. audiences — challenged that.

“The fact that there’s skepticism about whether this was real is people bringing that cynicism to live events,” she says.

For those of a certain generation, the incident brought to mind another notorious on-air slap — when pro wrestler Jerry Lawler struck comic actor Andy Kaufman on David Letterman’s show in 1982. Lawler and Kaufman had maintained a feud over Kaufman’s performances related to wrestling, and Kaufman had ended up in a neck brace after a wrestling match between the two.

A few months later, in the course of a joint appearance on Letterman, the wrestler stood up and whacked Kaufman across the face, knocking him out of his chair, neck brace and all. “It was not clear if the altercation was staged,” said one newspaper. NBC said at the time it received dozens of calls from viewers asking if the fight was real. (It wasn’t, though that wasn’t revealed until Kaufman was 10 years dead.)

And now we have Twitter (where Lawler posted Monday about the similarities), and instantaneous opinions, and a cacophony of declarative statements rather than phone calls to the network asking questions. As TV scholar Robert Thompson of Syracuse University’s Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture says, the skepticism is double-edged.

“Believing everything you see — especially in the technology era — is naive. But not believing anything ever, no matter how much evidence comes out — that’s equally unhealthy and debilitating,” Thompson says.

Yet in a nation where the “real” often proves to be fake, the “fake” can turn out to be real and we all join the masses in mass assumption along the way, how do you ever sort it all out? Particularly because, in the end, all of what happened Sunday night felt distinctly of a piece, whether real or fake or somewhere in between: There was a stage, there was an audience, and there were players.