WASHINGTON — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has given the smaller nation’s embassy in Washington an unexpected role: recruitment center for Americans who want to join the fight.

Diplomats working out of the embassy, in a townhouse in the Georgetown section of the city, are fielding thousands of offers from volunteers seeking to fight for Ukraine, even as they work on the far more pressing matter of securing weapons to defend against an increasingly brutal Russian onslaught.

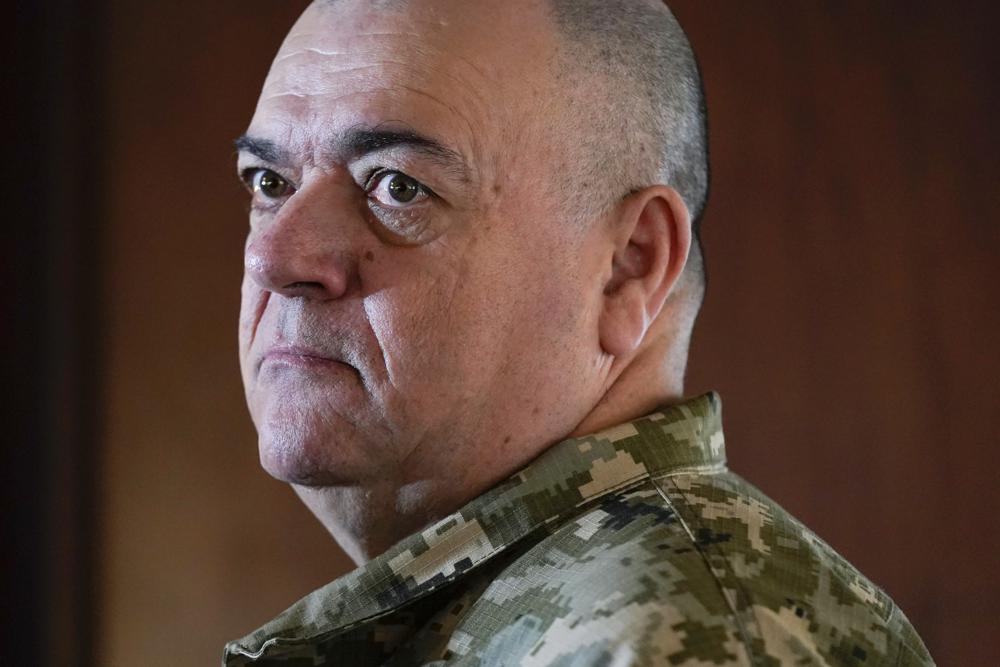

“They really feel that this war is unfair, unprovoked,” said Ukraine’s military attaché, Maj. Gen. Borys Kremenetskyi. “They feel that they have to go and help.”

“This is not mercenaries who are coming to earn money,” Kremenetskyi said. “This is people of goodwill who are coming to assist Ukraine to fight for freedom.”

The U.S. government discourages Americans from going to fight in Ukraine, which raises legal and national security issues.

Since the Feb. 24 invasion, the embassy in Washington has heard from at least 6,000 people inquiring about volunteering for service, the “vast majority” of them American citizens, said Kremenetskyi, who oversees the screening of potential U.S. recruits.

Half the potential volunteers were quickly rejected and didn’t even make it to the Zoom interview, the general said. They lacked the required military experience, had a criminal background or weren’t suitable for other reasons such as age, including a 16-year-old boy and a 73-year-old man.

Some who expressed interest were rejected because the embassy said it couldn’t do adequate vetting. The general didn’t disclose the methods used to screen people.

Kremenetskyi, who spoke to The Associated Press just after returning from the Pentagon for discussions on the military hardware his country needs for its defense, said he appreciates the support from both the U.S. government and the public.

“Russians can be stopped only with hard fists and weapons,” he said.

They must make their own way to Poland, where they are to cross at a specified point, with their own protective gear but without a weapon, which they will get after they arrive. They will be required to sign a contract to serve, without pay, in the International Legion for the Territorial Defense of Ukraine.

The Ukrainian government says about 20,000 foreigners from various nations have already joined.

Borys Wrzesnewskyj, a former Liberal lawmaker in Canada who is helping to facilitate recruitment there, said about 1,000 Canadians have applied to fight for Ukraine, the vast majority of whom don’t have any ties to the country.

“The volunteers, a very large proportion are ex-military, these are people that made that tough decision that they would enter the military to stand up for the values that we subscribe to,” Wrzesnewskyj said. “And when they see what is happening in Ukraine they can’t stand aside.”

It’s not clear how many U.S. citizens seeking to fight have actually reached Ukraine, a journey the State Department has urged people not to make.

“We’ve been very clear for some time, of course, in calling on Americans who may have been resident in Ukraine to leave, and making clear to Americans who may be thinking of traveling there not to go,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken told reporters recently.

U.S. citizens aren’t required to register overseas. The State Department says it’s not certain how many have entered Ukraine since the Russian invasion.

Under some circumstances, Americans could face criminal penalties, or even risk losing their citizenship, by taking part in an overseas conflict, according to a senior federal law enforcement official.

But the legal issues are only one of many concerns for U.S. authorities, who worry about what could happen if an American is killed or captured or is recruited while over there to work for a foreign intelligence service upon their return home, said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive security matters.

The official and independent security experts say some of the potential foreign fighters may be white supremacists, who are believed to be fighting on both sides of the conflict. They could become more radicalized and gain military training in Ukraine, thereby posing an increased danger when they return home.

“These are men who want adventure, a sense of significance and are harking back to World War II rhetoric,” said Anne Speckhard, who has extensively studied foreigners who fought in Syria and elsewhere as director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism.

Ukraine may be getting around some of the potential legal issues by only facilitating the overseas recruitment, and directing volunteers to sign their contracts, and receive a weapon, once they arrive in the country. Also, by assigning them to the territorial defense forces, and not front-line units, it reduces the chance of direct combat with Russians, though it’s by no means eliminated.

The general acknowledges the possibility that any foreigners who are captured could be used for propaganda purposes. But he didn’t dwell on the issue, focusing instead on the need for his country to defend itself against Russia.

“We are fighting for our existence,” he said. “We are fighting for our families, for our land. And we are not going to give up.”