WASHINGTON — State attorneys general and the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol are digging deeper into the role that fake slates of electors played in Donald Trump’s desperate effort to cling to power after his defeat in the 2020 presidential election.

Electors in seven battleground states signed certificates falsely stating that Trump, not Democrat Joe Biden, had won their states. They mailed those certificates to the National Archives and Congress, where they were ignored.

Now those certificates are getting a second look from lawmakers as they conduct an expansive review of the riot on Jan. 6, 2021, and the events preceding it. More than a dozen people have been subpoenaed so far.

A look at who the electors are, how the scheme unfolded and why lawmakers are investigating now:

Electors are people appointed by state parties, sometimes before the general election, to represent voters. The job is often given to current and former party officials, state lawmakers and party activists.

The winner of the state’s popular vote determines which party’s electors are sent to the Electoral College, which convenes in December after the election to certify the winner of the White House.

There’s very little guidance in the Constitution about the qualifications of electors except that no senator, representative or person holding federal office can be appointed to the position. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment also specified that state officials “who have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the United States” cannot serve as electors.

There are currently 538 electors, matching the number of U.S. senators and representatives, plus three for the District of Columbia, which gets those electoral votes even though it has no voting representation in Congress.

Once chosen to be an elector, members gather in their respective state capitals on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December to certify their statewide popular vote winner. Each elector gets two votes: one for president and one for vice president through a process laid out by the 12th Amendment.

To cast the votes, each elector signs six certificates. One gets mailed to the Senate president, two go to their state’s secretary of state and two go to the National Archives. The last is sent to a local judge.

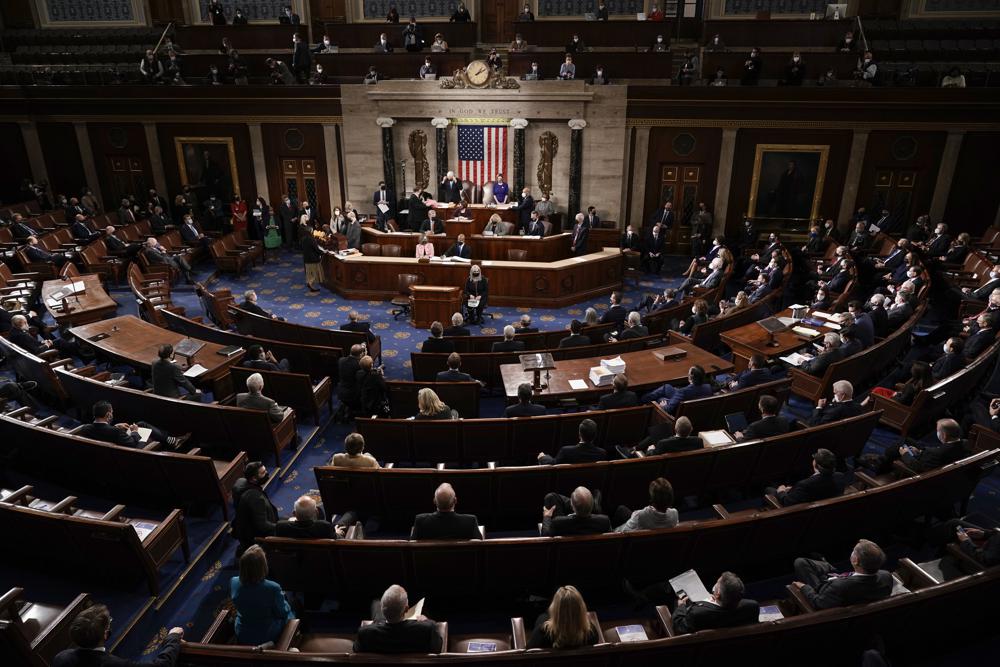

The sitting vice president — in 2021 it was Mike Pence — presides over the session and opens the vote certificates from each state in alphabetical order.

After the certificates are opened, they are passed off to four tellers — two from the House and two from the Senate — who announce the results. House tellers include one representative from each party and are appointed by the House speaker. At the end of the count, the vice president announces the name of the next president.

The certification of the results on Jan. 6, 2021, was upended as a mob of Trump’s supporters fought past police and broke into the Capitol, halting the process and forcing lawmakers and Pence into hiding. Biden’s victory in the Electoral College was certified in the early morning of Jan. 7 after it took police all day to clear the rioters and secure the building.

On Dec. 14, 2020, as Democratic electors in key swing states met at their seat of state government to cast their votes, Republicans who would have been electors had Trump won gathered as well. They declared themselves the rightful electors and submitted false Electoral College certificates declaring Trump the winner of the presidential election in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, New Mexico, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin,

Those certificates from the “alternate electors” in seven states were sent to Congress. Several of Trump’s Republican allies in the House and Senate used them to justify delaying or blocking the certification of the election during the joint session of Congress.