The plan includes several controversial proposals, and it’s unclear if it has any support among leaders on either side. But it could help shape the debate over the conflict and will be presented to a senior U.S. official and the U.N. secretary general this week.

The plan calls for an independent state of Palestine in most of the West Bank, Gaza and east Jerusalem, territories Israel seized in the 1967 Mideast war. Israel and Palestine would have separate governments but coordinate at a very high level on security, infrastructure and other issues that affect both populations.

The plan would allow the nearly 500,000 Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank to remain there, with large settlements near the border annexed to Israel in a one-to-one land swap.

Settlers living deep inside the West Bank would be given the option of relocating or becoming permanent residents in the state of Palestine. The same number of Palestinians — likely refugees from the 1948 war surrounding Israel’s creation — would be allowed to relocate to Israel as citizens of Palestine with permanent residency in Israel.

The initiative is largely based on the Geneva Accord, a detailed, comprehensive peace plan drawn up in 2003 by prominent Israelis and Palestinians, including former officials. The nearly 100-page confederation plan includes new, detailed recommendations for how to address core issues.

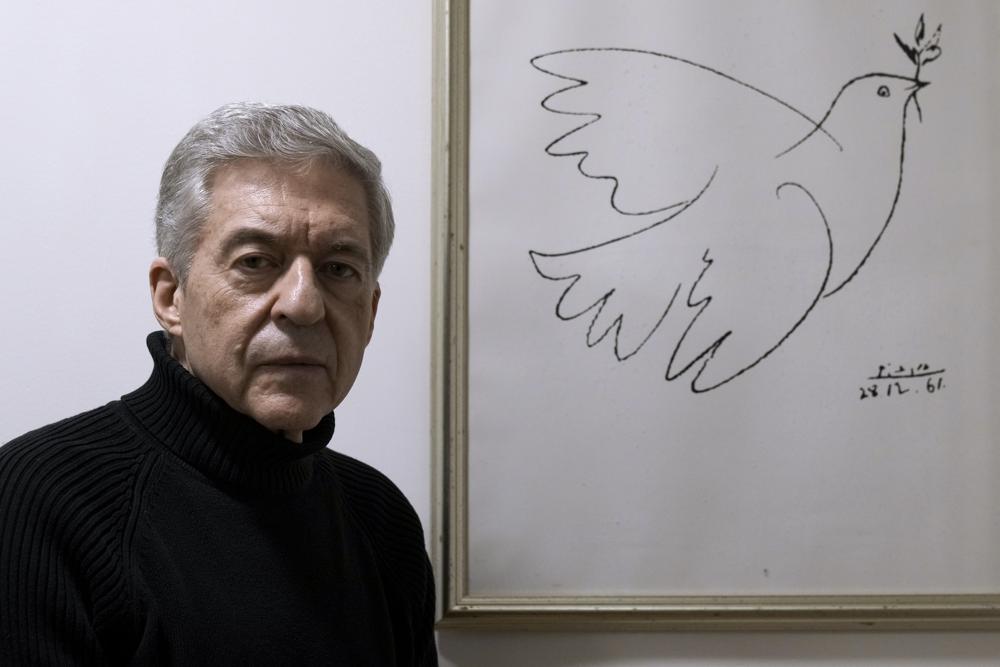

Yossi Beilin, a former senior Israeli official and peace negotiator who co-founded the Geneva Initiative, said that by taking the mass evacuation of settlers off the table, the plan could be more amenable to them.

Israel’s political system is dominated by the settlers and their supporters, who view the West Bank as the biblical and historical heartland of the Jewish people and an integral part of Israel.

The Palestinians view the settlements as the main obstacle to peace, and most of the international community considers them illegal. The settlers living deep inside the West Bank — who would likely end up within the borders of a future Palestinian state — are among the most radical and tend to oppose any territorial partition.

“We believe that if there is no threat of confrontations with the settlers it would be much easier for those who want to have a two-state solution,” Beilin said. The idea has been discussed before, but he said a confederation would make it more “feasible.”

Numerous other sticking points remain, including security, freedom of movement and perhaps most critically after years of violence and failed negotiations, lack of trust.